BBCSO/Brabbins, Barbican ★★★★☆

The centenary of Luigi Nono’s birth year is not being celebrated as widely this year as the radical Venetian composer deserves, although the challenges of such an undertaking are easy to understand. A few decades ago the BBC Symphony Orchestra might have devoted one of its famous annual monographic composers’ weekends to an exploration of Nono’s music, but instead of such three-day festivals it now offers some Total Immersion days: yet it still eschews offering a entire Nono event and instead placed him as part of an Italian Radicals program with four composers.

If that sounds more like a paddle than a full immersion, Sunday’s events were excellent programming. Nono and two other composers born in the 1920s, Bruno Maderna and Luciano Berio, were spotlighted alongside their slightly older contemporary Luigi Dallapiccola. Through film, a concert with musicians from the Guildhall School and lectures by Jonathan Cross (Professor of Musicology at Christ Church, Oxford) and Harriet Boyd-Bennett (Associate Professor of Music at the University of Nottingham), the day provided a rare exploration of the leading figures who shaped Italian music after World War II.

It was a politicized world, and they were radical both socially and musically. But no one was more politically committed than Nono, whose Canti di vita e d’amore formed the core of the evening’s main concert by the BBCSO. All of Nono’s works are a response to human suffering, yet all of his music ends in some kind of hope. The first of these three “songs” with orchestra commemorates Hiroshima and opens explosively; with four timpanists and a battery of other heavy percussion equipment, the burden is orchestral, but the excellent soloists Anna Dennis (soprano) and John Findon (tenor) held their own. Dennis was searingly intense in the unaccompanied center movement that summoned the Algerian resistance and was hauntingly joined by Findon in the final love song.

The other highlight was the chance to hear music by Maderna, a great figure of Italian modernism and former guest conductor of the BBCSO. His Oboe Concerto No. 3 (1973) was his last work, and perhaps in retrospect we can hear its upwardly floating textures as a parting word. Yet a playful opening, in which the solo oboe blows out high notes, is repeated in a more subdued manner at the end. Nicholas Daniel was superb, capturing the whimsical imagination of the work, and the orchestra’s shimmering sea of pointillist delicacy was beautifully controlled by conductor Martyn Brabbins.

Dallapiccola’s Three Questions With Two Answers, related to his opera Ulisse, is an impressive orchestral work that finds its own solution despite a final, unanswered question. A bit serious perhaps, but it still represents serialism in its most lyrical and Italianate form; all the composers mentioned were connected to the opera house in some way.

Berio could hardly have been represented without one of his solo Sequenzas (here Sequenza IXc, an arrangement for bass clarinet, growlingly sonorously performed by Thomas Lessels) or his celebrated Sinfonia. The Sinfonia was radical in 1968 and in some ways has not aged well, but it flowed strongly under Brabbins. The centrepiece, a re-covering of the scherzo from Mahler’s Second Symphony and some other musical highlights, remains undeniably brilliant and attracted a tour de force from the BBC Singers. YES

This concert will be broadcast on BBC Radio 3 on July 1 and will be available on BBC Sounds for 30 days

Game Music Festival, Southbank Centre ★★☆☆☆

Friday evening brought an unusual crowd to the Royal Festival Hall. Around the bar were excited groups of vaguely medieval-looking half-human beings who appeared to be friendly. I had a nice conversation with a High Elf Rogue, a Githyanki Fighter, and a Drow Paladin, all sipping healthy fruit juices. I haven’t seen so many pointy furry ears since that David Attenborough documentary about desert foxes.

These people dressed as characters from the video game Baldur’s Gate 3 were there for the Game Music Festival, a daylong celebration of what is quickly becoming one of the most heard music genres in the world. You would think that such a festival would feature a range of composers, but – for reasons that the music did not justify – each of the two concerts actually focused on just one composer. First the Argentinian-born Gustavo Santaolla, composer of the score for the dystopian horror-fest The Last of Us, and later the Bulgarian-born Borislav Slavov, who scored the neo-medieval game Baldur’s Gate 3.

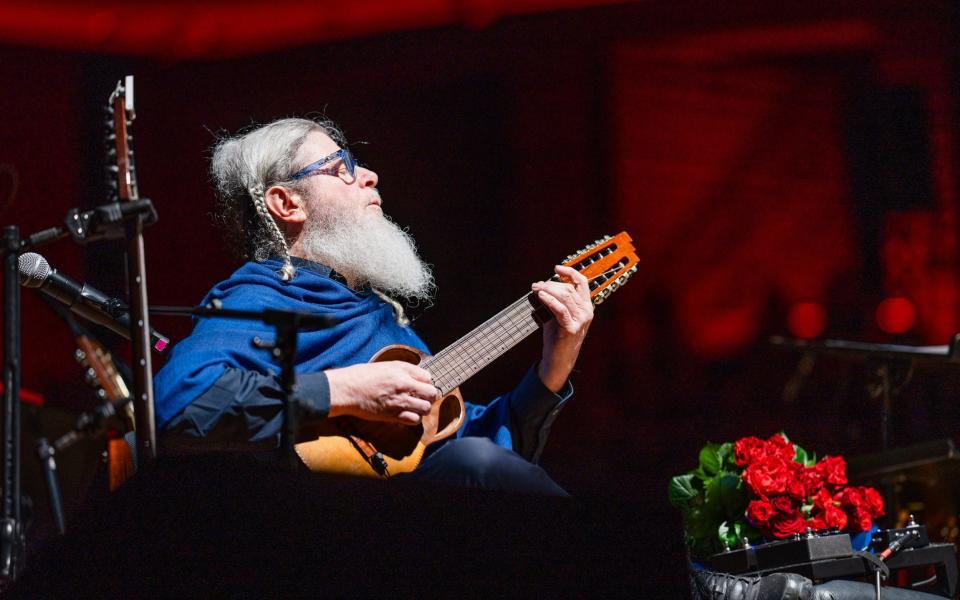

The earlier concert dedicated to The Last of Us at least had the virtue of some humble songs. Santaolalla was a singer-songwriter in several rock bands in the 1970s, and although he is now gray-haired and weak (he had to be supported as he gingerly stumbled onto the stage), he found the energy to play some sentimental ballads on his guitar . At one point he even sang a banging heavy rock song, which must have been completely foreign to the young audience, but which they loved anyway. The “atmospheric” moments between songs couldn’t have been more boring: single notes, sickly sliding strings, pounding “doomy” rhythms on drums.

Slavov’s music for Baldur’s Gate 3 evoked a very different world of dangerous quests through castle-strewn mountains. Two sopranos, Mariya Anastasova and Ilona Ivanova, sang a few songs in pale, androgynous voices that were just right for their vaguely Celtic “far away and long ago” quality.

Interspersed between these were chugging, dark numbers of the ‘let the battle begin’ type, and large heroic pieces reminiscent of vast landscapes fit for acts of daring. They’re painted in the kind of soaring horns and massive, simple harmonies familiar from John Williams’ film scores, but without the variation needed to make simplicity interesting. Phrases were always repeated verbatim, so instead of gathering energy, the melodies simply stopped when they ran out of power.

The Philharmonia Orchestra could have played such quadruple things in their sleep, but they showed their commitment so well that this kitsch-fest seemed almost enjoyable at times. IH