In the early 1960s, artist Charles Lutyens found himself in the middle of a crisis. After divorcing his first wife, Ariane, and losing custody of his two sons, Niels and Paul, obsessive thoughts consumed him.

These thoughts were expressed in works such as Corridor Encounter, a disturbing encounter with a bent over naked man, and The Maggot, in which he shows a walking male figure with a larva gnawing in his head.

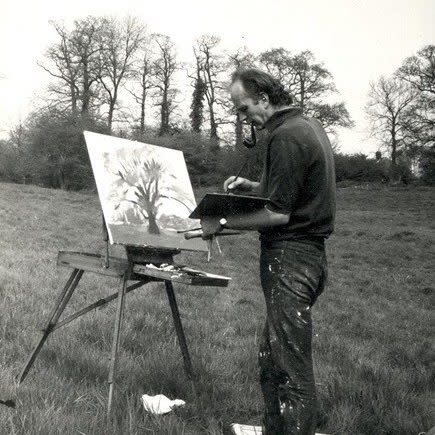

“It was like a maggot was chewing on his brain non-stop,” says Marianna, his second wife. She remembers that her husband – the great-nephew of Sir Edwin Lutyens, the architect behind the Cenotaph – was so preoccupied with his painting that he sometimes insisted on ‘going to sleep with his work, waking up with his work’.

Yet this is not the usual story of tragic artistic introspection. Lutyens used his own mental suffering for the greater good, working as a pioneering art therapist in a number of psychiatric institutions in Britain.

Now the work he made is at the heart of an exhibition called A World Apart, at the Bethlem Museum of the Mind in London, located in the oldest psychiatric hospital in the world (now in Beckenham). The photos – all on loan from Lutyens’ family – offer a glimpse into the hidden, often stigmatized world of mentally ill patients in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. Museum director Colin Gale says some of his works not only explore “people at the end of treatment” but also “reflect the inner workings of his own psyche”.

In many of the paintings and drawings he depicted the living environment of various hospitals. In the 3.5 x 1.5 meter psychogeriatric ward, painted in the mid-1970s, he shows a nurse with a teapot wheeling around in what looks like a drinks cart. On closer inspection, it’s a stroller with a baby inside, plowing through a sea of faces etched by sadness, fear and boredom.

Of course, the stigmatization went back centuries. Bethlem was used to house the insane as early as 1403, and in the 17th and 18th centuries it became infamous for entertaining the public. Its nickname, Bedlam, entered the Oxford English Dictionary as a “scene of extreme confusion, disorder or commotion” and was the setting of a 1946 horror film of the same name starring Boris Karloff.

Marianna recalls that Lutyens was uncomfortable with the way patients were ‘managed’ during this time. His daughter Joanna adds: “He was bothered by how blank people could look, and I imagine there was a lot of medication.”

Yet Lutyens managed to do something remarkable. In the hospitals and day centers where he practiced, he invited reluctant patients to draw anything on the page, even if it was just a single shape or color. Marianna says one patient made a small pencil mark in the center of the paper. “The person said, ‘If I’m asked or given something, I do the minimum.’ That would be the start of therapy for Charles. He was truly so gifted as an art therapist that he helped several people from hospitals to normal everyday life.”

Zelinda Adam worked with Lutyens at Harlow House, a psychiatric day hospital in Buckinghamshire. As a psychoanalytic psychotherapist, she says, “We try to reach the subconscious. Charles’ patients weren’t able to do that – as many patients aren’t – so art therapy was born, I guess. He always knew how to reach them.”

Adam describes Lutyens as ‘a gentle giant whose creativity seeped through every pore of his body. I’ve never really met a man like him.” Of his own art, she adds, “He had a way of getting right under the skin of the pain that is part of mental illness – what we in the business call the ‘nameless fear.’ If anyone could grasp the utter hopelessness, it was him.”

When I meet Professor Robert Howard in Bethlem, he is examining a large square painting by Lutyens entitled The Group. He says it is “extremely terrifying and evocative” and takes him straight back to his first job, in 1988, as a psychiatrist at Bethlem’s sister hospital, Maudsley.

The photo shows blank-faced men and women sitting awkwardly at the edges of a room. “There was a group like this every morning in the first department I worked in,” says Howard, now professor of geriatric psychiatry at University College London and curator of the Bethlem Museum. “I actually found it very difficult because some of the patients were very disturbed and psychotic, but the nurses just treated them as if they were fine. So if a patient was manic and behaving in a way that was completely inappropriate, the staff would embarrass him in front of the group, rather than taking it into account. It made me question whether I should become a psychiatrist.”

Prof Howard also got a glimpse of the primitive practices of the past. “Many of my patients were undergoing extraordinary treatment 40, 50 years before I met them – people who were diagnosed with schizophrenia in the 1940s and had frontal lobotomies. You asked for an MRI scan and when it came back all there was was a huge black hole where the front of the brain should be.”

I wonder what future generations will look back on with horror about today’s approach. “I think we would be more shocked about the people we don’t treat. We’re starting to look a bit like America: you know the mentally ill homeless people on the streets. One of the first things to be cut is the homeless team.”

Professor Howard also says that the art therapy he used to see in his department is now “a luxury” for the NHS. “We were lucky to have it. You’ll probably get it in the private sector. I’m not sure many NHS units would still have it.

In addition to helping the patients, the patients also helped Lutyens. When he began work in 1963 on an 800 square meter mural for the interior of the newly consecrated church of St Paul’s in Bow, east London – one of the largest mosaics in the British Isles by a single artist – he reached an impasse . He is unsure how to portray the heavenly host, angels he would only be able to see if he reached the throne of God.

He started thinking about the metamorphosis that sometimes took place during the group therapy sessions, for example “when someone comes in and is very closed, very dark, and doesn’t want to say anything,” Marianna explains. “When the inner self can recognize a truth, something happens – the arms are loosened and there can be a light in the eyes and a light in the face. This is what is angelic. And so he had his angel!”

Charles Lutyens died in 2021 at the age of 87, widely celebrated for the mural and for Outraged Christ, a 4.5 meter high wooden, iron and steel sculpture in Liverpool Cathedral. But his work with Britain’s psychiatric patients is equally to be cherished.

“He was an extraordinary man,” says Zelinda Adam, “and not many people knew that. But hopefully they will now.”

“A World Apart: The Work of Charles Lutyens” runs Saturday through August 31 (admission is free); museumofthemind.org.uk