When Hayao Miyazaki pitched “The Boy and the Heron” (GKids, now in select LA and NYC theaters) to Studio Ghibli co-founder/producer Toshio Suzuki in 2016, he asked permission to make the story about himself. This surprised Suzuki – his then friend of almost 40 years –; the legendary anime director isn’t known for getting so personal. And yet this fit perfectly with the idea that Ghibli films are dedicated to reliving memories.

“I agree that this is Miyazaki’s most personal film, because he actually told me,” Suzuki told IndieWire via Zoom through an interpreter. Not only is “The Boy and the Hero” inspired by Miyazaki’s youth (he endured the firebombing of Japan during World War II and his father was a director of the family’s aircraft factory), but also by his career at Ghibli with his two best friends: the late studio co-founder/director Isao Takahata (“Grave of the Fireflies”) and Suzuki.

More from IndieWire

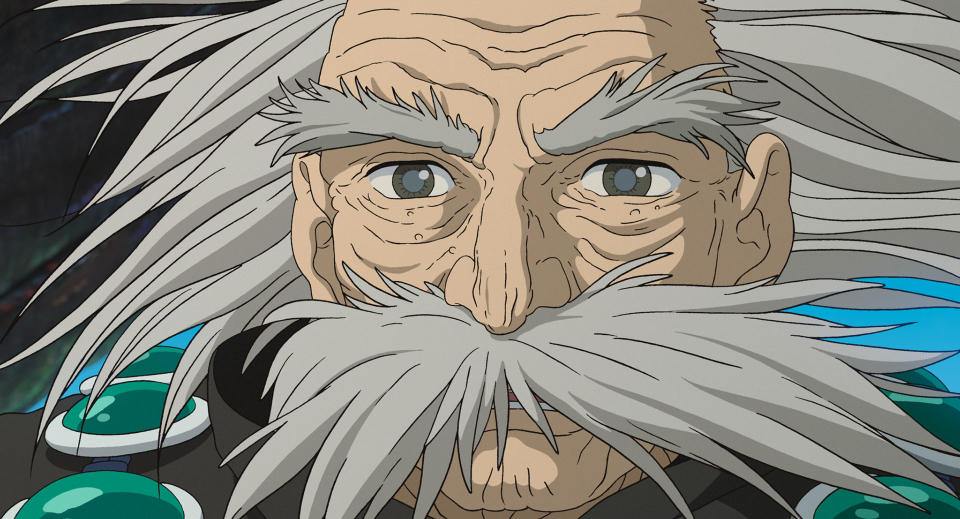

“Miyazaki is Mahito [the 12-year-old protagonist voiced by Luca Padovan in the English-language version]Takahata is the great uncle [voiced by Mark Hamill]and the gray heron [voiced by Robert Pattinson] is meSuzuki added. “So I asked him why. He said [Takahata] discovered his talent and added him to the staff. I think Takahata san was the one who helped him develop his skills. On the other hand, the relationship between the boy and the [heron] is a relationship in which they do not give in to each other, push and pull.”

All in all, there’s a lot to unpack: Miyazaki came out of retirement for the second time after ‘The Wind Rises’ (2013) to make his twelfth feature: the semi-autobiographical, hand-drawn fantasy for his grandchildren. It’s about destruction, loss and rebuilding a better future through imagination, inspired by the novel he loved as a child (“How Do You Live?”).

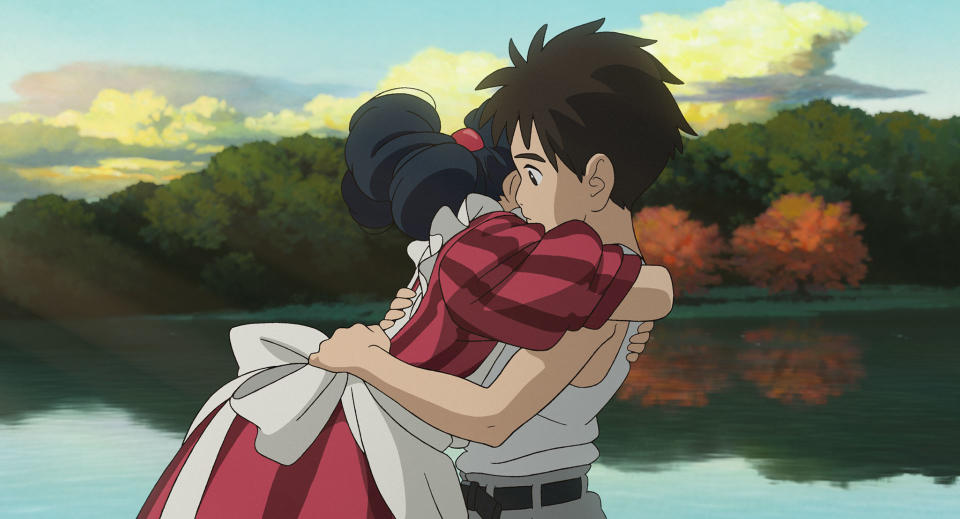

Mahito loses his mother in the firebombings in Japan and moves to the countryside, where his father (voiced by Christian Bale), who runs an air munitions factory, marries his sister-in-law Natsuko (voiced by Gemma Chan). Traumatized, angry and confused, the boy encounters a talking heron (part bird, part human), who tells him that his mother is still alive and leads him to an alternate world in a magical tower shared by the living and the dead. There he meets his great-uncle, the architect of the tower, and is reunited with both his mother (voiced by Karen Fukuhara) and Natsuko.

Initially, Suzuki resisted greenlighting “The Boy and the Heron” because of Miyazaki’s age (he’s 82) and the high cost (it may be Japan’s most expensive film, but has the equivalent of nearly $80 million earned at the country’s box office). Still, Miyazaki quelled his resistance with his enthusiasm and impressive storyboards. The film took seven years to complete, and Suzuki had to hire some of Japan’s most talented animators outside of Ghibli to handle the task (including supervising animator Takeshi Honda of “Neon Genesis Evangelion” fame). With reduced stamina and poor eyesight, Miyazaki could not oversee production in the same way as when he was at the height of his creative powers and relied on Honda to draw, redraw and review under close advice.

But with Takahata’s death in 20018, a grief-stricken Miyazaki was forced to dial back the role of the great-uncle in the story, who previously played a more central role in the boy’s life. “After Takahata died, he couldn’t continue with that story, so he changed the story and it became the relationship between the boy and the heron,” Suzuki continued. “And in his mind the Heron was initially something that symbolized the eeriness of the mansion and that tower, even ominous, that he goes to in time of war. But he turned it into a kind of budding friendship between the boy and the heron.”

Miyazaki first toyed with the idea of exploring the theme of friendship in “The Wind Rises” (inspired by real-life combat designer Jiro Horikoshi during World War II) before abandoning it. “So this time, when the Heron became the center of the story and he came up with the storyboards, I made sure he didn’t portray me in a bad way,” Suzuki said. “That said, I have known Miyazaki for 45 years. I remember everything about him. There are things that only I know. There are things that only the two of us know. And he remembers all those little details, which I was very impressed with.”

For example, when Mahito and the Heron are chatting in the house of Kiriko (voiced by Florence Pugh), a younger, seafaring version of one of the old maids, it’s a recreation of the way Miyazaki and Suzuki would meet. “The place where we have our meetings, where we have our conversation, is in his studio, his studio,” he added. “And he has a big table, but we don’t sit across from each other, we sit next to each other, and we never look at each other when we talk. And what we discussed was very similar.”

During production, Suzuki became impatient when he saw the new storyboards featuring the great uncle. It seemed like Miyazaki was deliberately hesitating while mourning Takahata. “My question was, ‘When will the great uncle show up?’” Suzuki said. “He built this great character, but he never appears in the storyboards he would bring to me. But it took about a year after Takahata’s death before he was able to draw that character into the storyboards in the second half of the story.

“And the most surprising thing for me was when I saw the storyboard where Mahito was asked by his great uncle to continue this work, this legacy, and he says no – he turns down the offer. Miyazaki was someone who followed Takahata’s path for years, and I thought it was a big thing for him [to follow a different path].”

Meanwhile, Suzuki confirmed that Miyazaki has not retired. The film has given the director renewed confidence to continue working on other stories. However, Miyazaki cannot focus on new ideas as long as “The Boy and the Heron” remains in theaters. “He needs to clear his head again,” Suzuki said, “and then when he clears his head with a blank canvas, he usually comes up with new ideas. So we have to wait a little longer.”

The best of IndieWire

Sign up for the Indiewire newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.