There are still some interesting residual effects to be seen from the recent nosedive to Earth of the European Remote Sensing satellite, or ERS-2.

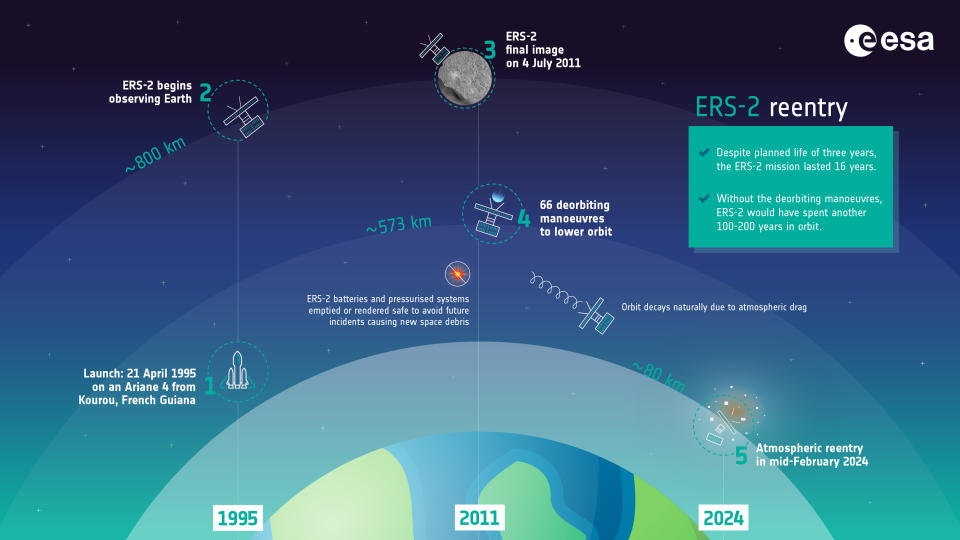

After its launch in April 1995, ERS-2 studied our planet for almost sixteen years. Then, in 2011, the European Space Agency (ESA) has decided to end the mission of the radar-guided spacecraft. The agency commanded a series of deorbit maneuvers, lowering the satellite’s average altitude and reducing the risk of collision with other satellites or other satellites. space debris.

The spacecraft was also “passivated” to reduce the risk of fragmentation. Passivation involves removing internally stored energy, such as releasing unused propellant and discharging batteries (which, if left charged, can cause an explosion).

“There can be no intervention from the ground, so ERS-2 will return completely naturally – now a common occurrence as on average one spacecraft re-enters the Earth’s atmosphere per month,” according to a pre-fall statement from ESA. However, the term ‘completely natural return’ is arguably a user-friendly replacement for ‘uncontrolled’.

Related: The largest spacecraft to fall uncontrollably from space

After the fall

ESA’s Space Debris Office predicted that ERS-2’s return would occur on February 21 at 10:41 a.m. EST (1541 GMT). In reality, the spacecraft made its dive about two hours later and re-entered the atmosphere over the North Pacific Ocean.

The European Space Operations Center (ESOC), home to engineering teams that operate spacecraft in orbit, noted that the previous forecast had a plus or minus value of 1.44 hours.

Yet in the uncontrolled space junk industry, minutes – even seconds – count. They can make the difference between a piece of space debris falling into isolated ocean waters or crashing into a populated area.

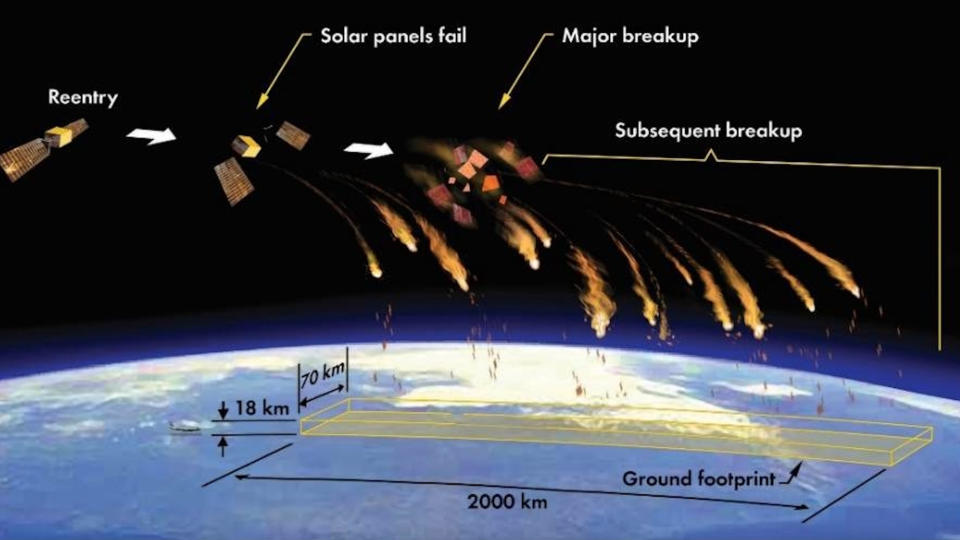

In fact, it is likely that parts of the 2.5-ton ERS-2 survived the fiery reentry. On average, between 10% and 20% of the mass of larger objects passes through the atmosphere and hits the ground or water, said Simona-Elena Nichiteanu, an ESOC media relations officer.

Before the fall of ERS-2, Nichiteanu told Space.com that the largest and heaviest pieces that could survive relatively intact are four spacecraft tanks, a trio of internal panels that support spacecraft instruments and the antenna structure for the satellite’s Synthetic Aperture Radar antenna, possibly the largest piece, assuming it didn’t fall apart.

But we’ll probably never know how much of the bus-sized ERS-2 survived, given the location of the reentry.

“No damage to property was reported,” said an ESA statement after the fall of ERS-2.

Related: Large, doomed satellite seen from space as it tumbled toward a fiery reentry on February 21 (Photos)

Willy-nilly satellite falls

But the knowing nature of a satellite that has gone out of control falls is reason for the willies.

That’s the view of Ewan Wright, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of British Columbia and junior fellow of the Outer Space Institute. He is actively focused on the sustainability of the space environment.

In the future, Wright told Space.com, all major satellites should make controlled reentry.

“Operators need to keep them under control so they can get back above the oceans, away from people, planes and ships,” says Wright. “ERS-2 re-entered the North Pacific. If it had re-entered half an hour earlier, it could have hit Europe or Africa,” he said.

And in the North Pacific, air traffic travels between Asia and North America, and to Hawaii, Wright points out.

“Fortunately the planes were not affected this time,” he said. “Even if aircraft are not affected by space debris, the uncertainty could lead to airspace closures and route diversions, costing airlines and passengers money.”

There’s also ship traffic to worry about – and not just in the final reentry zone, given the speed at which objects move in orbit. It is possible that pieces of disintegrated satellites could fall over much of the objects’ return trajectory.

According to cruiseradio.net, there was indeed a report of an ERS-2 warning about debris on a Princess Cruises ship with 2,200 passengers on board. The vessel, Island Princess, was informed by a coordinated message from ESA and the National Hydrographic Office that the ERS-2 targets and targets could enter the area the pleasure boat would cross en route to Port Luis, Mauritius . The island princess left the area and took a different course.

For Wright, the premise is this: “We shouldn’t rely on luck to reduce the risk of casualties. Instead of rolling the dice, operators should use controlled reentry, where satellites are steered away from people and aircraft return.”

Global standard

Darren McKnight is a senior technical fellow at LeoLabs, a commercial provider of space domain awareness services low Earth orbit mapping based in Menlo Park, California.

McKnight said the chance of casualties on the ground in a single return is small. However, the overall risk increases over time.

“It is not a matter of ‘if’, but rather ‘when’ an abandoned object will survive the Earth’s surface and result in significant damage, fatality or injury,” McKnight told Space.com.

And when that fateful day arrives, there will be an uproar over the uncontrolled return of satellites, McKnight said. The “global standard” is the 25-year rule – meaning every satellite must be deorbited within 25 years of the end of its mission, he added.

“But the US is the only country that requires operators to minimize the risk of casualties upon return to the ground,” McKnight said. “This will evolve just as the 25-year rule evolves into a five-year rule, a rule currently only required by the Federal Communications Commission.”

Old rules

On the other hand, we will have decades of re-entry based on the old rules, McKnight said. Furthermore, he believes, most of the desolate mass currently in orbit consists of objects launched in the 1980s and 1990s, when mitigation rules did not exist at all.

The slower the regulations evolve, the more complicated it will be to determine their benefits since there is a mix of hardware in circulation, McKnight said.

“I also think it’s interesting that with regulations aimed at incentivizing operators to design the spacecraft for demise and ensure it disintegrates upon reentry, some people are now concerned about polluting the atmosphere. ” from the effluents of space launches and disintegrating spacecraft re-entering,” McKnight noted.

According to McKnight, that situation is becoming increasingly complicated as the amount of material grows and grows. “No one will be happy!” he said.

Hot topic

RELATED STORIES:

— Two large pieces of space junk almost collide in the “bad area” of space

– European satellite falls to Earth during milestone ‘assisted reentry’

— The Kessler syndrome and the space debris problem

Dead satellite traps like those from ERS-2 are fairly common, says Leonard Schulz, a researcher at the Institute for Geophysics and Extraterrestrial Physics at the Technische Universität Braunschweig in Germany.

Such reentries will only increase in the future, Schulz told Space.com, due to the growing number of objects being launched into low Earth orbit. In addition, the effects on the atmosphere due to spacecraft reentrya current topic that ESA is also evaluating.

“Today we lack information on many aspects when it comes to released materials and subsequent effects on the atmosphere,” Schulz said.

Re-entering satellites is a good opportunity to collect data with measurement campaigns, Schulz advised. However, uncontrolled returns like that of ERS-2 are extremely difficult to observe, he said, because the uncertainty level of where the satellite actually returns is so high.

“But controlled reentry offers great measurement opportunities,” Schulz concluded, “which should be a focus in the future!”