Just before the 1907 Beijing to Paris motor race, The Economist – always prescient in its predictions – castigated ‘those who had rushed with such unfortunate enthusiasm to invest in bus companies’, emphasizing that ‘the horse passes the test triumphantly ‘. .

I owe this quote to Kassia St Clair’s delightful new book, Race to the Future, which charts how this strange collection of adventurers captured the public’s imagination and helped transform the car from just an experimental novelty into a means of transport for the masses. who changed the world forever.

As Warren Buffet has noted about the advent of the automobile, it may not have taken long for the countless different car companies that sprang up around this time, the vast majority of which went bankrupt, but it certainly would have been wise to run short of horses

To be fair to The Economist, it is largely human nature to scoff at the shock of the new, and even to resist its adoption, given even half a chance.

“Who wants to hear actors talk?” said Harry Warner, one of the founders of the Warner Brothers film studios, before rejecting proposals for films with sound in 1927.

In a similar vein, Lord Kelvin, President of the Royal Society, declared in 1895 that “flying machines heavier than air are impossible”. As for computers, don’t even get started. “I think there is a world market for perhaps five computers,” said Thomas Watson, chairman of IBM, in 1943.

And so forth. Overall, we tend to resist change, especially when it is shoved down our throats. Established industry players are even less likely to embrace it.

All this brings us to the electric vehicle (EV). In the case of electric vehicles, we can be a little more confident in our predictions, if only because governments around the world have forced the end of the internal combustion engine. Like it or not, it will become virtually impossible to buy a new fossil fuel car in ten to fifteen years.

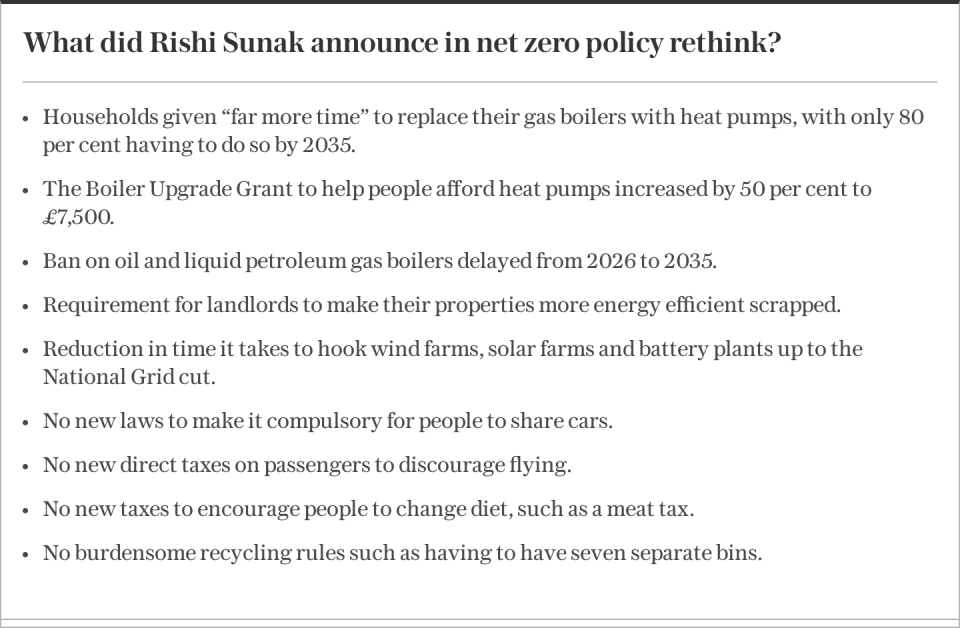

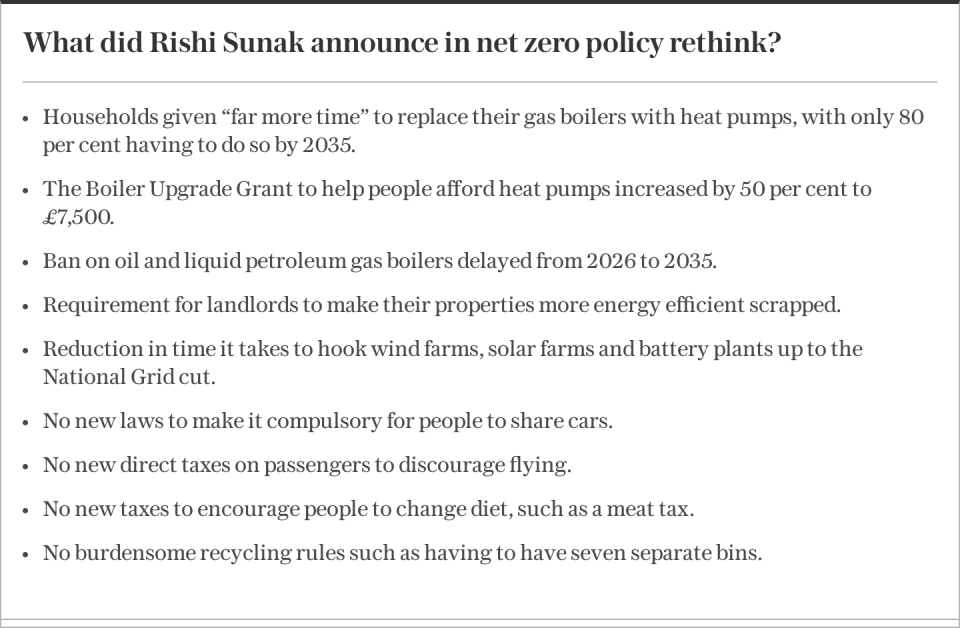

Downing Street likes to think of itself as the friend of motorists. In an effort to appease those who don’t want to give up their trusty old car for love or money, it recently pushed back the date for the phaseout of the internal combustion engine by five years to 2035.

This may ease the transition path somewhat for some automakers, but overall it won’t make much of a difference.

The so-called Zero Emission Vehicle mandate still requires 22% of all new cars sold in Britain next year to be zero-emission, rising to 80% by 2030. Making traditional petrol or diesel cars is quickly becoming unprofitable if it is limited to such a small part. from the market.

Any company that wants to stay in the game must therefore move quickly to electric vehicles, as Nissan declared late last week with a heavily subsidized £2 billion investment to make its Sunderland factory fully electric by 2030.

This is clearly good news for the economy, and sets aside earlier warnings that the forced march towards electric vehicles sounded the final death knell for car production in Britain.

Nissan’s announcement comes on the heels of BMW’s £600m investment in an electric Mini, and Jaguar Land Rover’s plans for a £4bn gigawatt battery factory in Somerset.

Fears that increasing trade barriers with the European Union would shift all future EV investments to the continent appear unfounded; It appears that the benefits of Britain’s flexible labor market outweigh the rules of origin and other export market barriers that came with Brexit.

Nevertheless, it remains true that EVs must become price competitive to take the next step and gain mass market appeal. As things stand, the infrastructure to support them is also woefully inadequate.

Tesla’s Model Y was Britain’s best-selling car in June this year, but with prices starting from around £45,000 this is still a product reserved for well-heeled enthusiasts.

Surveys show that there is a hardcore market of about 25 percent of households that are almost evangelical in their desire to own an electric car.

At the other extreme, there is still about a quarter of car owners who would not buy an electric car under any circumstances, although it is unfortunately possible to actuarially map out the likely future decline of this mainly older group of traditionalists.

For the middle majority, the main deterrents revolve around price and ‘range anxiety’ – the fear that the car won’t have enough battery power to reach an available charging point.

In any case, after many years of electric car sales consistently exceeding most expectations, the pace of growth has slowed significantly, prompting the Office for Budget Responsibility last week to lower its forecast for electric car use from 67 % of all new car sales in 2027 to 38 pc.

The high upfront cost of electric vehicles compared to internal combustion engine vehicles is deterring many potential buyers, the OBR concluded, especially among those using car finance, which has become more expensive due to higher interest rates.

Charging at home can mean significantly lower running costs, but there is little or no benefit to external charging, if you can find a charging point at all.

Fears that the price of traditional vehicles are about to increase to help meet EV quotas are increasing the incentive to buy the old technology now while you can.

In other words: the transition will not take place as quickly as previously thought. In the meantime, electric vehicles may pose a wider existential threat to the UK and European economies.

In its plans to become the world’s leading supplier of cars, China has largely skipped the fossil fuel development phase and gone straight to electric cars, some of which are already starting to become price competitive with the traditional European car industry, and therefore a could have a real mass industry. – market appeal.

Taking on Chinese competition crucially depends on how quickly companies like Nissan can scale up production to drive down unit costs. Technology is also changing rapidly. Solid state batteries potentially offer advanced global manufacturers a real opportunity to return to the top.

The challenges that established manufacturers face in switching to electric powertrains are one thing, but the transition also poses a significant problem for the government, which currently spends around £25 billion a year, equivalent to 1% of GDP collects fuel taxes.

The last chancellor to propose road pricing as an alternative – Alistair Darling in 2005 – was dismissed with a flea in his ear after an online poll showed overwhelming opposition from motorists on grounds of privacy alone.

However, the problem with taxing the price of electricity is that it would penalize other uses of electricity. It would be difficult to distinguish. Moreover, higher CO2 taxes can only be a temporary solution.

No wonder ministers are reluctant to talk about how to close the gap. Yet decisions cannot be postponed forever.

Broaden your horizons with award-winning British journalism. Try The Telegraph for 1 month for free, then enjoy 1 year for just $9 with our exclusive US offer.