Around the turn of 1924, all of musical New York was stunned at the prospect of an ‘Experiment in Modern Music’. The venue was the extremely luxurious Aeolian Hall, and the famous Paul Whiteman Band performed. It wasn’t quite the first experiment in combining jazz and classical music; Whiteman had recently caused a stir by mixing songs by modernist composers such as Schoenberg, Milhaud and Bartok with jazz songs by Irving Berlin, Jerome Kern and Gershwin.

But this happened on a larger scale. Whiteman had commissioned a new concert for solo pianist and jazz band from the man of the moment, 25-year-old George Gershwin. He already scored a huge success in Tin Pan Alley with songs such as Swanee and Stairway to Heaven, and wrote the much-discussed ‘Jazz Opera’ Blue Monday.

The opera was actually a flop, but the fact that it existed at all was further proof that the early 1920s was a moment of liberation and ‘breaking boundaries’ in music. The romantic musical plush of the period before the First World War had been banished. Thanks to the economic boom, this was a hedonistic new era that gave rise to wild experiments in art, which some called the Machine Age, others the Jazz Age. As Whiteman himself put it: “Jazz develops new forms, new colors, new technical methods, just as America is constantly throwing aside old machines for newer and more efficient ones.”

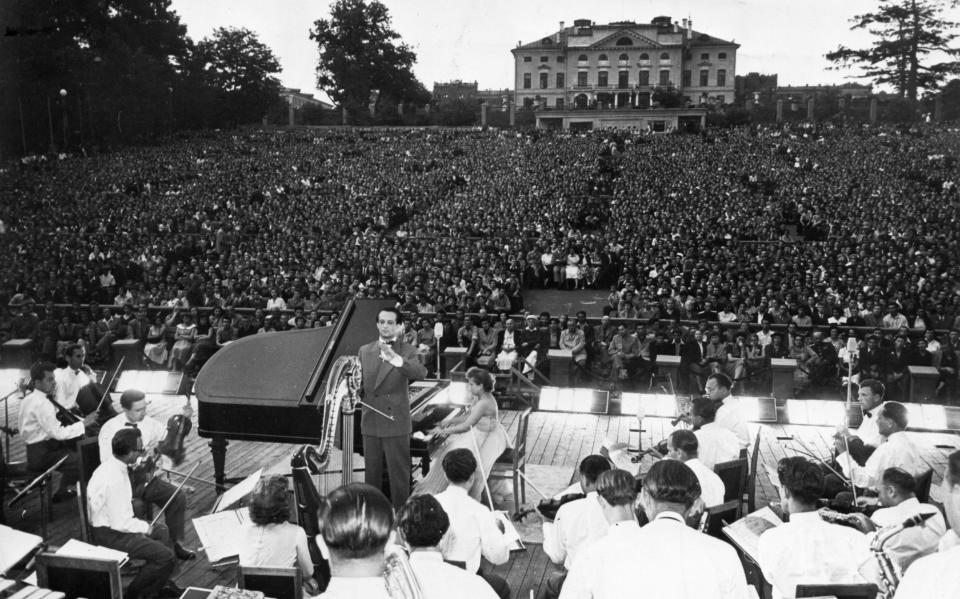

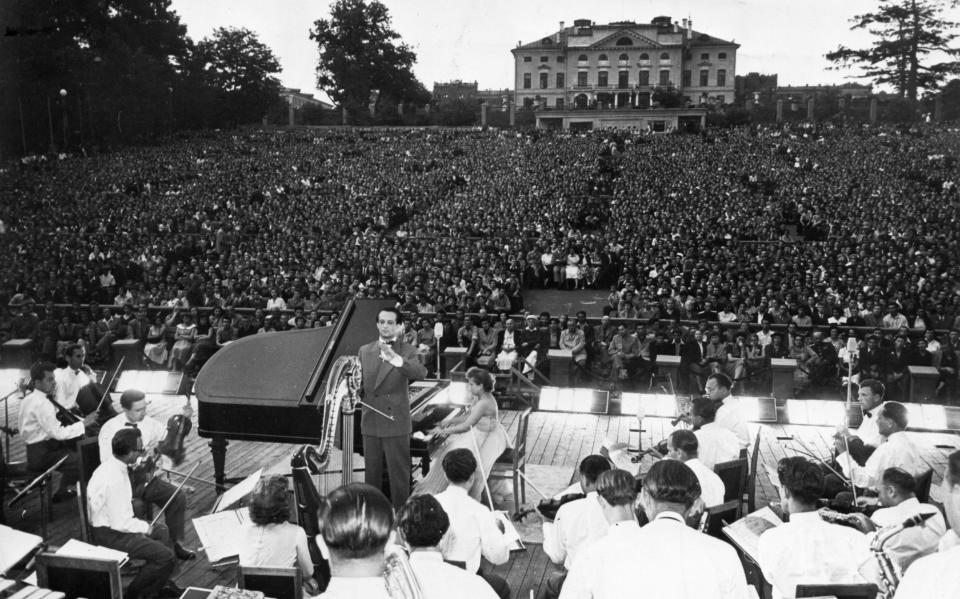

No wonder a glittering audience showed up on that snowy night of February 12, 1924. The ‘March King’ John Philip Sousa, the virtuoso pianists Leopold Godowsky and Rachmaninov, the conductor Jascha Heifetz and the composers Ernest Bloch and Igor Stravinsky were all there. The evening started with a surprisingly old-fashioned speech from Whiteman, in which he said that the concert would be a “stepping stone for the masses to enjoy symphony and opera.”

Then came a strange mix of recent blues hits, comedy songs like ‘Yes! We Have No Bananas’, piano novelties, a Russian selection including Rachmaninov’s famous C minor Prelude, and ‘light music’ numbers by operetta composer Victor Herbert. Finally came Gershwin’s Rhapsody, with the composer himself at the piano, and for the first time ever the piece’s insanely horny clarinet wail sounded.

The audience loved it, but the critics weren’t so sure. Despite some praise for the exuberance and originality of the music, as well as for Gershwin’s virtuoso skills as a pianist, the general criticism was that the piece was formless – “just one damn thing after another.” That is not literally true. The piece works something like a one-movement symphony, with a large opening movement dominated by a gloriously stirring idea that owes much to James P Johnson’s ‘stride piano’. Then follows a lighter Scherzo with a Trio (often cut), a heart-warming slow movement with that immortal “big tune” and a Finale that leads to a return of the stride piano idea.

It looks good on paper, but it’s undeniably small to hear. Most listeners won’t mind, because the actual material is so irresistible – especially that big, stirring tune at the beginning, with its vampy step-piano accompaniment, and the big romantic melody towards the end, which sounds like Rachmaninov spiced with brutality on Broadway. .

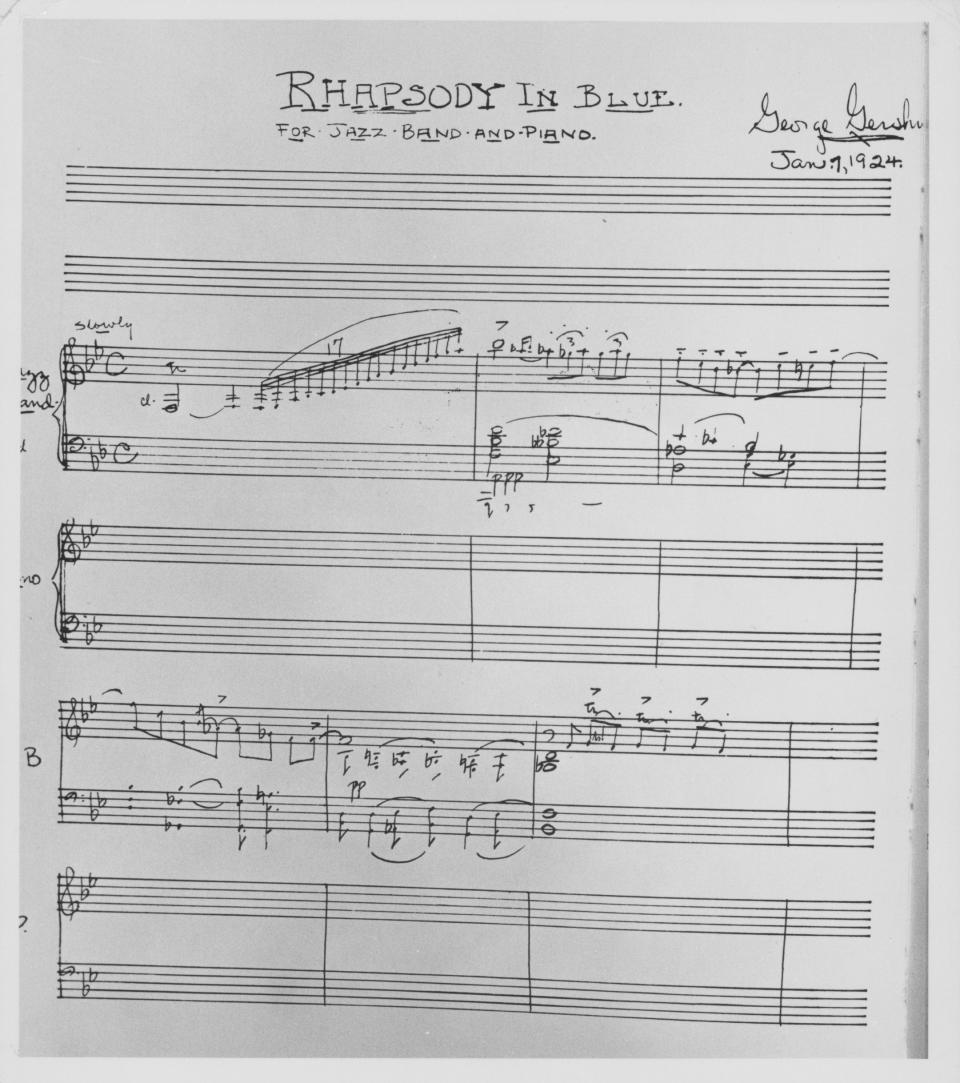

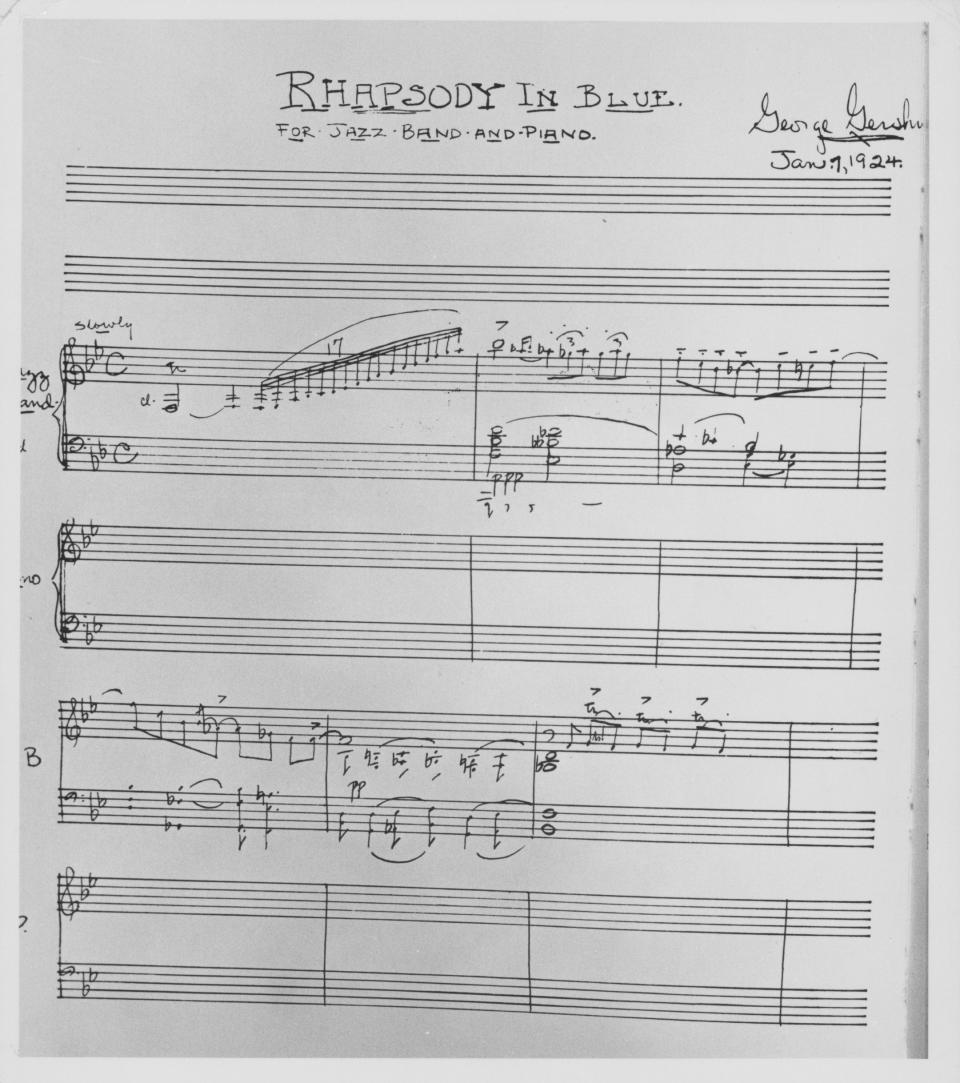

Given the inventiveness of the actual music, perhaps we should embrace the quixotic nature of the piece, which would change from one performance to the next in its early days. This quality is captured in the score itself, which exists in countless versions. There is the version for two pianos that Gershwin wrote at top speed in January 1924, having completely forgotten about Paul Whiteman’s commission until he read about the upcoming premiere in a newspaper (probably not true, as are the countless stories about who did what this piece contributed – legendary premieres have a way of producing legends).

This was followed by a number of orchestrations by Ferde Grofé, the first for jazz band, the second for theater pit orchestra, and then the one most of us know, for symphony orchestra. Then there are the countless vastly shortened versions that retain only the melodies (a cunning trick by Gershwin, as he could register the piece as a ‘song’ and claim more royalties), and the rearrangements such as those made for a United airline advertisement in 1987.

A new layer of creative unpredictability has been added by the pianists who recorded the work, not least Gershwin himself, whose two versions differ considerably. Leonard Bernstein introduced some of his own pieces, but still managed to stretch the tempo of some sections so far that his version is actually longer than many.

Then there are the very interesting jazz versions, which imbue the written score with improvisation. Glenn Miller’s version dethrones the pianist in favor of trumpeter Bobby Hackett and adds the swing element that had always been missing until then. Ellington goes even further in ‘swinging’ the piece and turns it into a real big band piece with prominent solos for his star players such as clarinetist Harry Carney, trumpeter Cootie Williams and tenor saxophonist Paul Gonsalves.

So yes, that premiere in 1924 was a red letter in music history – but what music exactly? Does it belong in the history of the virtuoso piano concerto? Or should we see it more as a piece of exciting musical modernism? That might be a better starting point, since the premiere took place during a concert with the grand title “An Experiment in Modern Music.” Or is it part of the history of jazz – again a reasonable assumption, since the premiere was given by perhaps the best-known jazz band in the country at the time? Or even the history of dance music, since much of the music plays in a foxtrot rhythm?

History has given us the answer. Gershwin’s piece captured that magical historical moment when a fusion of modernism, jazz and classical music seemed possible. Therefore, it briefly spawned a host of imitations, including Gershwin’s own Concerto in F, Ravel’s Piano Concerto, and George Antheil’s Jazz Symphony. But the moment passed. By the 1940s, with the advent of bebop, jazz had lost its popular power and became an art form in its own right. Gershwin’s Rhapsody became increasingly captivated by the classical world, so that we now get performances that follow the final orchestral version to the letter, in a spirit of “authenticity”.

To me this reveals something essential about the piece. Perhaps the best gift we could offer, the Rhapsody in Blue at 100e Birthday would mean giving up authenticity and encouraging pianists and conductors to play fast and loose with the score, as musicians used to do. It would outrage the purists, but restore the luster to this most sympathetic masterpiece of the 20th century.

Sunday Feature: American Rhapsody can be seen on Radio 3 on Sunday, February 11 at 6:45 p.m.