Jwala Singh wipes away a tear as he sits in his office, surrounded by cricket trophies, and recalls a vow he made on the day his father died. “I have promised myself that one day I will become an India player.”

He has remained true to his word, to the detriment of the England team. Singh is the coach of Yashasvi Jaiswal, the scorer of a double hundred in the second Test last week and one of the brightest young batting talents in the world.

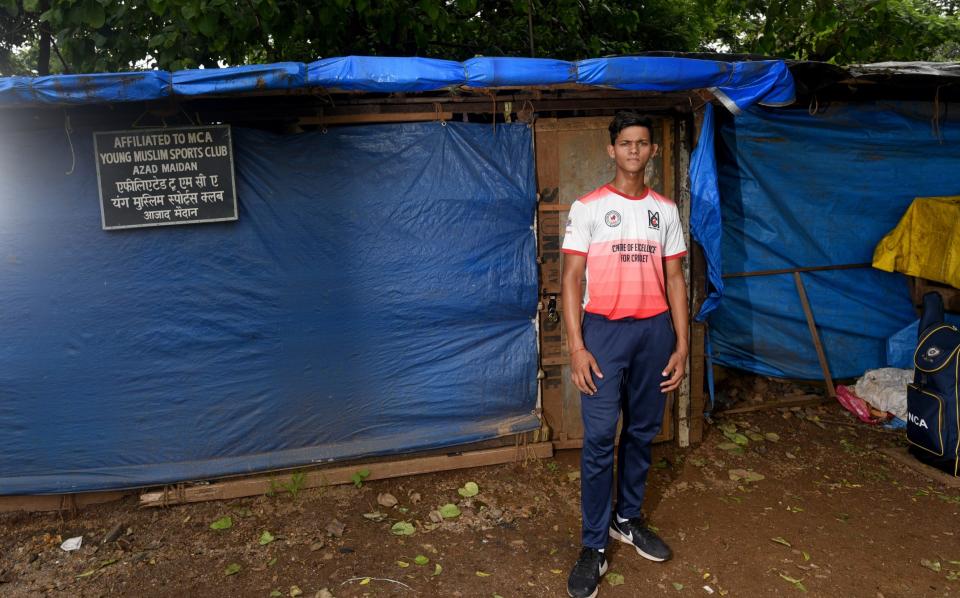

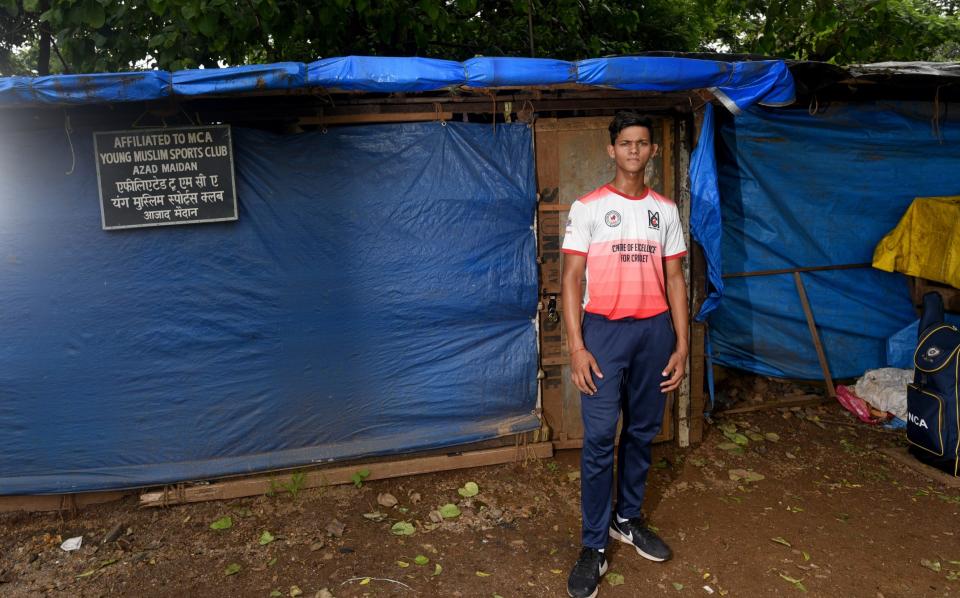

What started as a plan to chronicle Jaiswal’s rise from sleeping in a tent on the Azad Maidan in South Mumbai to the India team and IPL stardom turns into a story of two men, coach and student, as their journeys on the path of life are equally remarkable.

During a three-hour journey through Mumbai, Singh shares his story at several stops along the way to the Azad Maidan, where we end our conversation and he points to the spot where he first met a 12-year-old boy who helped him fulfill his promise to his dying father.

“We were playing on one of the fields here and when the match was over I went to chat with a friend,” he says. “There were two batsmen in the nets. One complained about the pitches and complained about the groundsman, saying how could he hit it? The other was a small left-hander who batted brilliantly, without a word of complaint.

“I asked, ‘Who is that boy?’ My friend said, ‘Jwala, he has a lot of problems. He left his family behind in his village. He loves cricket and I’m afraid something bad will happen to him.’ Suddenly the batsman came up to me and I said, ‘What’s your name?’ He said, ‘Yashasvi Jaiswal. I live in this tent.’ I said, ‘Where’s your family?’ I was in shock that he lived alone. I don’t like to talk about someone’s poverty because I have experienced it. His story is also my story.”

From that chance meeting, the young Jaiswal would move in with Singh and live with him and his wife until 2022. He still turns up at the Air India Sports ground, almost at the end of the runway at Mumbai airport, where Singh now has his academy and has spent many hours coaching Jaiswal up to speed.

As we talk, the Azad Maidan is very busy. At least 10 matches will be played on this small triangular plot of ground on Thursday afternoons, and Singh points to the pitch where Sachin Tendulkar and Vinod Kambli scored their world record schoolboy partnership of 664. There is a bat-maker, who recently repaired, wood-sanded Jaiswal’s bat. A street food vendor wheels his cart to the side of the ground, ready for the lunch rush on panipuri and sugarcane juice. It was a street vendor like him who asked Jaiswal to help sell his street snacks to the players for a few rupees pocket money.

The groundskeeper’s tent where Jaiswal lived for two years, which had no electricity and would flood during the monsoon, has been swallowed up by a construction site as Mumbai’s relentless growth eats away at its historic virgins.

On one side is the Bombay Gymkhana, where India’s first Test match was played and you need an invitation to enter. We are on the north side, near the spot where Mahatma Gandhi once addressed thousands of people during the 1931 uprising in India. Azad actually means freedom in Persian. The freedom to pursue a dream connects Jaiswal with his coach, as both left small villages in the state of Uttar Pradesh as boys to make a name for themselves in Mumbai.

Singh moved to Mumbai in 1995, hoping to learn from the legendary Ramakant Achrekar, Sachin Tendulkar’s coach. “I was a really big fan of his,” he says. He takes us to the place where he lived for three years, where he slept in a mosquito-infested room in a gymnasium that he had to leave at five in the morning when people came in to exercise.

“My father was a vet and earned about 600 rupees a month (about £60 then) and he took out a loan, gave me money and told me to make a name for myself in Mumbai. He was criticized a lot for making me leave the village and come here. I decided that after two years I would no longer accept money from my family.”

Singh was a fast bowler and the lack of strength and conditioning advice and undoubtedly sleeping on the floor of a gym took its toll and injuries ended his hopes after playing cricket at the state level. “I collapsed injured one day and that was the worst day of my life. My dreams were over that day. I had no money for surgery. I didn’t dare talk to my family. If I tell them, they will say come back to the village because I was good at studying. After those injuries, I started coaching kids and making money.

“Then one day my father called and said he had grade four cancer. That was September 14, 2009. I was completely broken. I thought I had to take care of my father and asked him to come to Mumbai to live with me. He came for two months and on November 10 he died. Then I took my pledge to become an India player. I gave myself five years to find someone else I would leave cricket for good.”

It took only a year, not five, for his path to cross Jaiswal. There were difficulties early on. Jaiswal was banned from playing in local matches because someone forged a birth certificate for him so that he could register with the local cricket authorities. “The hardest part was that he was mentally weak and upset. People blackmailed him because of that birth certificate. They said if you play, we will show this certificate to the association and you will go to jail. That was what he said to me. That’s why he said, ‘I don’t want to play, I’m going to jail.’ I said I would take care of it.”

Jaiswal played in a Harris Shield tournament, an inter-state school competition and scored 47 runs and took five wickets. “I said to him, ‘Did the police come? Did you go to jail?’ “No sir,” he said. I said, ‘I am with you and will take care of it.’ He played in his next match and scored 319 not out in a three-day match. His father came to meet me. I said Yashasvi can live here and stay with me and I promise to help him with everything. His father became very emotional. He said he was here to take him back to the village. He said, ‘We are helpless. We can’t help my boy anymore. Now you are his father, mother and guardian. You take care of him. You decide what you do. You own his life.” They left him at my house. From there I started working with him.”

In time, Singh became Yashasvi’s legal guardian. We travel to his first house, now used as a hostel by the current intake at his academy, and he shows us Yashasvi’s old bedroom. Right now, a jumbo jet is taking off from the airport, just steps away, and it’s hard to hear each other talk. We then move to Singh’s current home where there are photos of them eating cake and more trophies. Also large trophies that require two hands to pick up.

“He lived with us as my son. I would get up early and put him on the floor. When there were matches, he would start hitting the nets at nine in the morning, he would play the game and then he would score again on his own, he was that hardworking. One day I took him to a store to buy a file for his newspaper clippings. He went in and bought a very small file. I said that’s not good. I went inside and asked the shopkeeper for the largest file he had. He filled it in two years.”

Jaiswal never needed much technical help. He was naturally gifted and Singh mainly talks about his temperament. “He wanted to hit for a long time. He made a lot of big scores. That’s his way.” In 2019, Jaiswal scored 203 in a 50-over match. He made 171 on Test debut, 209 against England and scored three other first-class double hundreds.

Others helped too. Singh credits former Indian players Dilip Vengsarkar and Wasim Jaffer as mentors and also Jaiswal’s IPL team, Rajasthan Royals, for their valuable input. Singh’s academy has now coached more than 300 boys and takes children from the villages as well as those who can afford it on scholarships. Prithvi Shaw, currently out of the Indian team, was one of his strikers and Hamza Sheikh, who plays for Warwickshire and was a victim of the obstruction fiasco while playing for England in the Under-19 World Cup last week, has regularly worked alongside Singh – which shows a text message he sent to Hamza’s father three years ago saying he would play for England Under-19s one day.

The day of Jaiswal’s Test debut last July in the West Indies was the highlight of Singh’s work, but he was in Britain and could not watch as his academy was on tour to play several leading public schools.

“I know this sounds very candid, but by then I knew he would be playing for India. That was my confidence in him and his hard work. I always told him where I left my cricket, you start your journey. We made sure he didn’t face the same hardships when he came to live with us and thanks to his hard work he made it to the top.”

The heat of the sun suggests that it is lunch. But Singh is busy watching the cricket on the Maidan. “I’m only 41. I still have twenty years to go. I want to make 11 Indian players.”

There is a young boy, not much older than 12 years old, who is enjoying hitting. He’s half the size of his adult teammates, but clearly a step up. Is he next? “This is why I come back to Azad Maidan. They come in every day, on the train for a long time. There are no sight screens, not much grass, each game follows the other. If you can stand out here, you have great power. Yeah, this guy’s good, let’s take a look.

A chance meeting. Thus began the Jaiswal story. Maybe another one is starting.