Astronomers have discovered that a small moon of Saturn, called Mimas, may harbor a hidden liquid ocean beneath its thick icy shell and thus have the conditions for habitability.

This shocking finding radically changes the definition of what an ocean moon can be, and could ultimately redefine our search for extraterrestrial life on moons in the solar system. That’s because Mimas – nicknamed the ‘Death Star’ because a large crater means it resembles the Empire’s space station in Star Wars – doesn’t at first glance look like the kind of body scientists would expect to support an ocean. In fact, it seems completely incapable of supporting such a huge amount of fluid.

The team behind the watery discovery estimates that the ocean lies about 20 to 30 kilometers beneath Mimas’ icy crust surface; the researchers also believe it is relatively young, only appearing between 2 million and 25 million years ago. Yet, despite being hidden for millions of years, the ocean appears to cover at least half the moon’s volume.

“The key finding here is the discovery of habitability conditions on an object in the solar system that we would never, ever expect to have liquid water,” Valery Lainey, a discovery team member and scientist at the Observatoire de Paris, told Space. com. “It’s really amazing.”

Related: Saturn’s moon Enceladus harbors an important ingredient for life

The discovery makes Mimas even more similar to its Saturn moon brother Enceladus, which scientists already knew has a subsurface ocean. Both moons are at similar distances from the gas giant planet and are similar in size: the ice-covered Enceladus measures about 310 miles (500 kilometers) in diameter and the similarly icy Mimas is slightly smaller at 246 miles (396 km) in diameter.

A key difference between the two moons is that while Enceladus’ ocean breaches the surface in the form of huge jets and plumes, Mimas’ sea has yet to crack its icy crust.

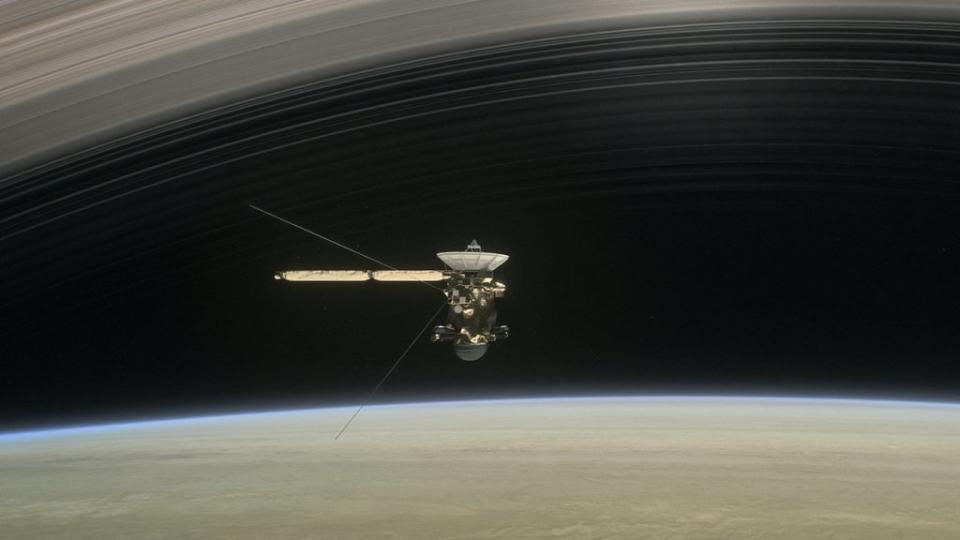

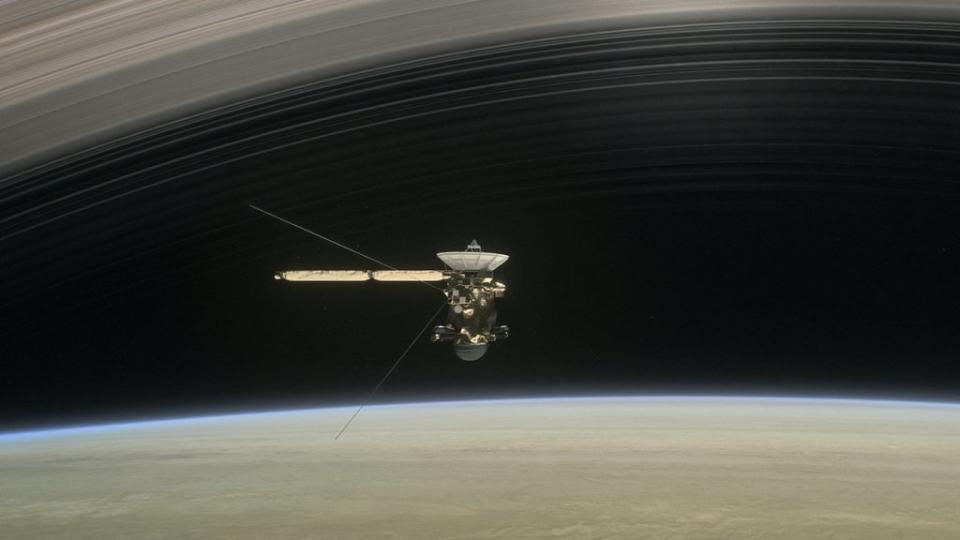

That means that while NASA’s Cassini spacecraft was able to fly through ice plumes from Enceladus to confirm the oceans and even discover some of the complex molecules within them, the spacecraft was unable to do anything like that for Mimas.

“It’s really surprising that we didn’t see anything, but the thickness of Mimas’ icy shell is enough to sustain this ocean for millions of years without any significant activity,” Lainey continued. “That’s why Cassini didn’t find anything on the surface of Mimas.”

However, that doesn’t mean that Cassini, which spent 13 years in Saturn’s system before purposefully crashing into the gas giant in 2017, didn’t play a key role in the discovery of the Mimas ocean.

Mimas’ ‘wobble’

Lainey and colleagues discovered their first clues that Mimas had a buried liquid ocean when they used Cassini data to investigate a break in Saturn’s infamous rings called the “Cassini division.”

While trying to discover whether a change in Mimas’ orbit could have caused the Cassini division, the team noticed a strange shift in both the moon’s rotation and its orbit. The team determined in 2014 that these large librations were either due to Saturn’s moon having a deformed, solid rocky core – or to a subsurface ocean that allowed the outer shell to oscillate independently of the core.

The breakthrough came when the team finally modeled Mimas’ motion and determined that for a rocky core to be responsible for the observations, it had to be elongated and flat like a pancake. Obviously this didn’t match what the team saw in real life, but furthermore, the way Mimas’ orbit has evolved since 2014 also provided support for the global subsurface ocean hypothesis.

“There is no rigid interior that could be compatible with the rotation and orbital evolution of Mimas,” Lainey said. “It’s a relief to finally succeed in demonstrating that that is the solution.”

A drenched moon

Not only was the team able to determine that the oceans have only been around for a few million years (due to the fact that Mimas’ orbit remains oblate, or eccentric), but the crew was also able to calculate how much water is likely present. in the oceans of the moon.

“At least 50% of Mimas’ volume is filled with liquid water,” Lainey said. “This is a huge amount of liquid water for the size of the satellite.”

This water appears to rub against the rocky core of Mimas and at the same time be heated by the friction this action generates. This interaction also gives rise to what Lainey describes as “interesting chemistry” likely to be developing on Saturn’s moon at this time.

Interactions between water and rocks are believed to have played a crucial role in the origin and persistence of life on Earth, meaning that such chemistry at Mimas is indeed an exciting prospect for research into life and habitability in the solar system.

“Mimas is a small object that looks extremely cold, with no geological activity, and you would never expect any geophysical activity inside, such as heating, or contact between water and with silicates in the rocky core,” Lainey said. “It’s really amazing that this is happening.”

For future research, Lainey said he would like to land a spacecraft on the surface of Mimas, or even on Enceladus.

“I’m pretty sure that any space mission to Enceladus will also visit Mimas, because they are extremely close, and they are extremely similar ocean systems, but at different times in their evolution,” he explained.

But with NASA’s planned Orbilander set to leave Earth in 2038 and arrive at the latter moon in 2050, such a project will be a long time coming.

RELATED STORIES:

– Signs of life shooting from Saturn’s moon Enceladus could be detectable by spacecraft, scientists say

– Methane in the plume of Saturn’s moon Enceladus could be a sign of extraterrestrial life, study suggests

— Saturn: Everything you need to know about the sixth planet from the sun

In the meantime, Lainey plans to survey Mimas from Earth to learn more about how temperatures evolved, how the presence of this ocean affected the orbit of Saturn’s moon, and what effect it had on the rings of Saturn and the other parts of the gas giant. mane. This could help better calculate the age of Mimas’s oceans.

“I would like to emphasize that Mimas absolutely does not look like the kind of property that could be habitable,” Lainey added. “So maybe the conclusion is that if this object can be habitable, who knows what other types of objects could be habitable?”

The team’s research was published Wednesday (Feb. 7) in the journal Nature.