In the summer of 2017, a delegation of visitors from the United Arab Emirates flew to the town of Reading in Berkshire.

They had come not for a tour, but to discover how scientists at the university were making progress in controlling the weather.

Earlier that year, the University of Reading had received a $1.5 million share from a $5 million fund allocated by the UAE Research Program for Rain Enhancement Science.

Now members of the UAE program had arrived to observe the first results of a project that was, quite literally, designed to make it rain.

While most Britons would prefer to see scientists working to stop the rain, drier parts of the world – including the UAE – understandably have different goals.

Accordingly, the five-strong team from Reading’s Department of Meteorology investigated how spraying an electrical charge into clouds could cause rain in areas where very little rain falls.

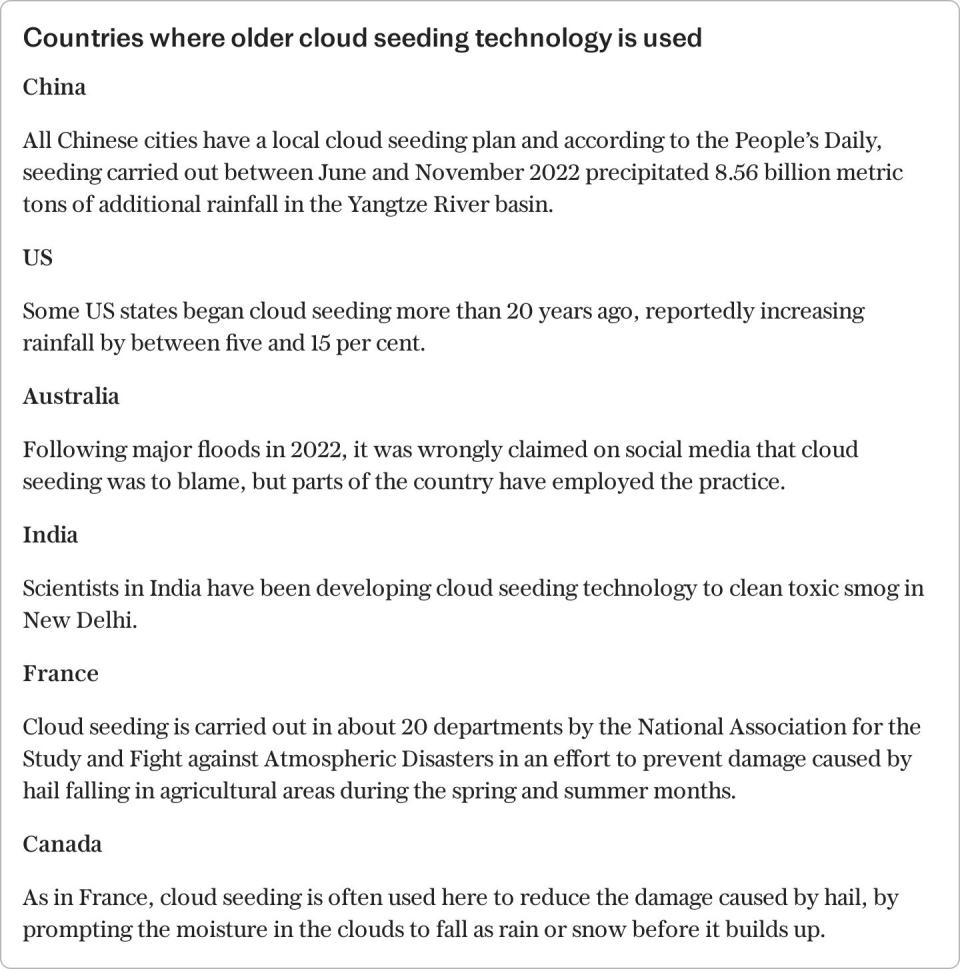

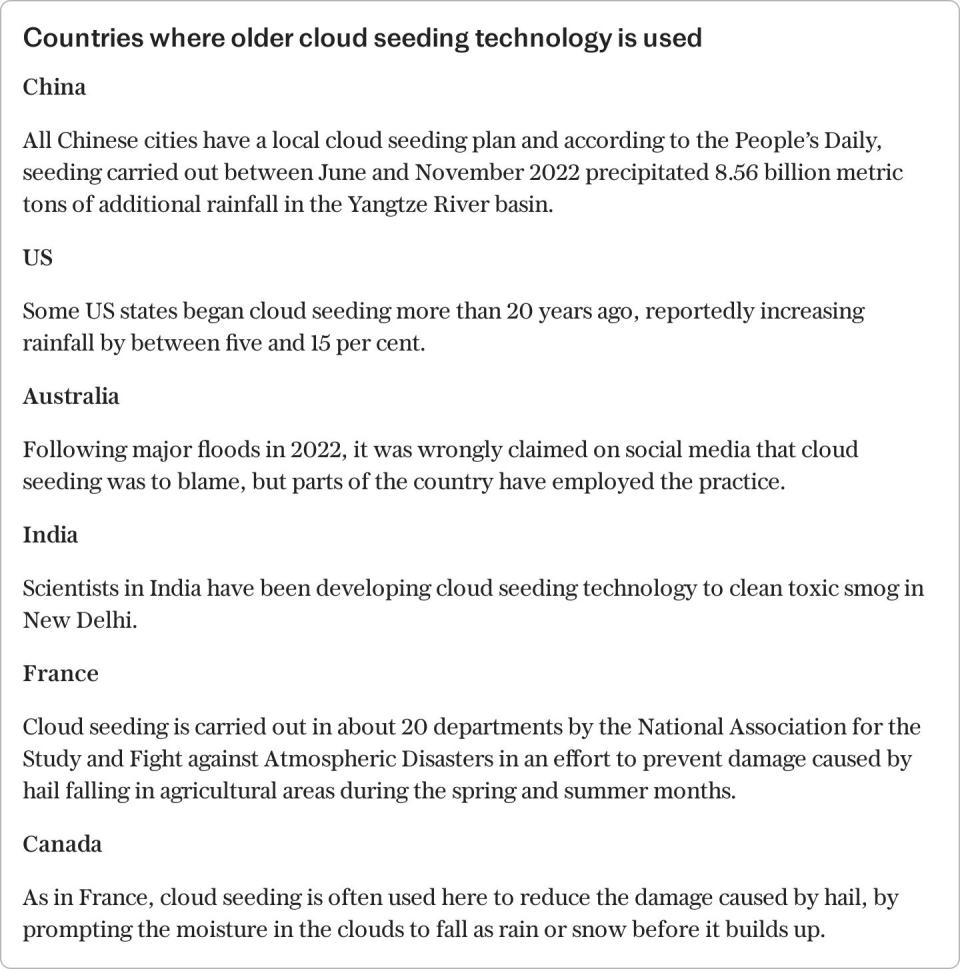

The idea of effectively playing God to influence the weather is not new. Already in the UAE and elsewhere, older ‘cloud seeding’ technology is being used – a practice of manipulating existing clouds to help deposit more rainfall.

Generally, it involves dispersing fine particles, such as silver iodide, salt or dry ice, into the clouds to help water vapor condense and turn into rain.

The plan being developed by the Reading scientists involves using drones to release electrical charges into clouds. Dry areas such as the Middle East and North Africa could benefit from this, the university says.

If it sounds like science fiction, previous iterations have been around since the 1940s, with the UAE using cloud seeding extensively since the early 2000s.

But this week, as record flooding causes chaos in Dubai, the practice is in the spotlight. If cloud seeding was used to create rain in the UAE, could it have been the cause of the rare downpour in Dubai that saw a year’s worth of rain fall in one day?

The short answer was no, it almost certainly couldn’t be. “The UAE has an operational cloud seeding program to increase rainfall in this arid part of the world,” said Prof. Maarten Ambaum, a meteorologist from Reading University.

“However, there is no technology that can create or even seriously alter this type of rainfall.” There had been no recent cloud seeding operations in the area, he added, and there would have been no benefit from cloud seeding that was predicted to bring significant rain anyway.

“The [weather] system was identified in our global model, which does not include any input on weather changes,”

says Grahame Madge, climate spokesperson for the Met Office.

“So at least the system was a natural phenomenon.” In the usually arid Gulf state, where temperatures can soar to 50 degrees Celsius in summer, planes regularly undertake cloud seeding. They reportedly use salt material components.

The Reading scientists, led by Prof. Giles Harrison, have now developed a different technique, which uses an electrical charge to make droplets stick together and quickly grow large enough to fall as rain. A bespectacled expert in atmospheric physics, Harrison harbors a long-standing fascination with the natural sciences – and an enthusiasm for testing new ideas.

The technology he and his team have developed has not been tested in the deserts of the Gulf states, but in the rather greener English countryside. In 2020, an initial experiment was carried out at the university’s farm in Sonning, Berkshire, by Harrison’s team, along with mechanical and electrical engineers from the University of Bath, releasing charge into the mist using electrical emitters.

The following year further testing was carried out at Bottom Barn Farm near Castle Cary in Somerset. Here, above a green landscape that rarely suffered from drought, unmanned aerial vehicles with specially developed charge emitters that could release positive or negative ions on demand were launched into another misty sky.

It was, Dr Keri Nicoll of Reading wrote afterwards, “an important first step in determining whether cloud droplet charging could be useful in helping rainfall in water-scarce parts of the world”.

The test flights showed that fog droplet size can be changed by charging, “which ultimately means it may be possible to use charge to influence cloud droplets and thus rainfall,” Nicoll wrote.

She said The national one, a UAE newspaper: “What we are doing here is something completely different. We use very small aircraft, which means it’s actually much more cost-effective, and we just charge what’s already there.”

The promise behind droplet or particle charging was that the technique could work well alongside the existing cloud seeding operation, making it more efficient at producing rain, she said.

According to the United Nations, approximately 2.3 billion people worldwide live in water-scarce countries, while 3.2 billion people live in agricultural areas with severe water shortages or scarcity.

Reading scientists hope that research into the properties of clouds and rainfall can ultimately help prevent conflicts over water in such places and provide enough water for a growing world population.

The Reading scientists have also carried out field work on desert rainfall and the effects of sea breezes in the Gulf, sending specially instrumented weather balloons through the fog of Abu Dhabi.

The technology they have developed has yet to be deployed operationally. But, Ambaum says of its potential future benefits: “Any small improvement in rainfall in dry areas will be of value.”

In the UAE, it is hoped the innovation could help the state grow its own crops and produce fresh water.

However, there is a caveat. “Note,” says Ambaum, “that if there are no clouds, you can’t have cloud seeding. That excludes many arid areas in the world.”

While the scientific consensus is that the cloud seeding already used in the UAE would not have caused the flooding, are there any other risks associated with this practice? Ambaum suggests not.

It occurs on small spatial scales (the size of individual convective clouds) and on short time scales (about an hour or so, the time during which microphysical effects of clouds occur). “Any interventions are therefore very limited in space and time,” he says.

“This is not a change in the weather. We cannot change the evolution or intensity of weather systems… It is also not climate engineering: any effects are limited in time and space.’

Moreover, the materials used for cloud seeding have very low concentrations and do not cause any adverse health effects, he adds.

The electrical charge used in the team’s research does not release any material into the environment at all, and because the drones used to release the charge are battery-powered, no pollution is created from the aircraft’s propulsion. The released charge disappears naturally.

“This means that Harrison and his team have developed a more environmentally friendly method of weather modification, which could in principle work automatically from multiple locations,” the university says.

As for the cause of the Dubai floods, the answer may seem more familiar.

“When we talk about heavy rainfall, we have to talk about climate change,” says Dr Friederike Otto, senior lecturer in climate science at Imperial College London.

“If people continue to burn oil, gas and coal, the climate will continue to warm, rainfall will continue to become heavier and people will continue to lose their lives in floods.”