Few islands capture the British imagination as much as Pitcairn. It is the beautiful but desolate rock in the Pacific Ocean where the mutineers of HMS Bounty hid, and where their descendants have been torn by infighting, tragedy and crime for hundreds of years.

Today, however, islanders have more prosaic concerns: Wi-Fi, for example. Of all the twists and turns in Elon Musk’s career, saving Pitcairn may be the most surprising. Simon Young, the Yorkshire-born mayor who became the first non-indigenous Pitcairner to hold the position when he was elected in 2022, says that thanks to Starlink, Musk’s satellite internet service that delivers high-speed connections to even the most remote places, Pitcairn residents are enjoying of renewed optimism about the future.

“It’s been a game changer in terms of communications,” says Young, 59, speaking via Zoom – another recent luxury – from his office in Pitcairn, which takes 13 days to reach from Britain. “We join the rest of the world.”

It’s a welcome change from all the bad news. Starlink means you could potentially move to Pitcairn and work remotely, watch Netflix and keep in touch with relatives on the other side of the world. The results were immediate.

“In the past month we have received five applications to the council from people wanting to settle,” added Young, who has been a permanent resident since 1999. “It’s unprecedented.”

Five applications may not sound like mass migration, but it is a significant percentage considering the total population is just 40 – the equivalent of five million people applying to join Britain in one month. “Our demographics are aging,” says Young, with more than a third of the population over 65. “Repopulation is at the top of our list of strategic objectives. We have changed legislation to encourage that and made land more available.”

This internet-fueled increase in immigration isn’t the only good news. Young has also focused on making Pitcairn a haven for scientific research. In addition to inhabited Pitcairn, there are three uninhabited neighboring islands: Henderson, Ducie and Oeno, with plenty of ocean surrounding them. In 2015, the British government voted to create a marine reserve around them, the largest in the world at the time at 324,000 square kilometers (it is still the third largest). Young has followed up by establishing a science center, which he hopes will encourage regular research trips.

“It’s absolutely pristine water because we’ve never had commercial fishing and there’s no tourism development,” he says. The progress was detailed in a recent article in New scientist magazine with the headline “How the infamous Pitcairn Island became a model for ocean conservation.”

Every step in the right direction is welcome. Young is understandably keen to paint an optimistic picture, but the only British overseas territory in the Pacific is used to being in the news for the wrong reasons. For years it looked as if the population was doomed, eventually succumbing to demographic change and the weight of its tragic past.

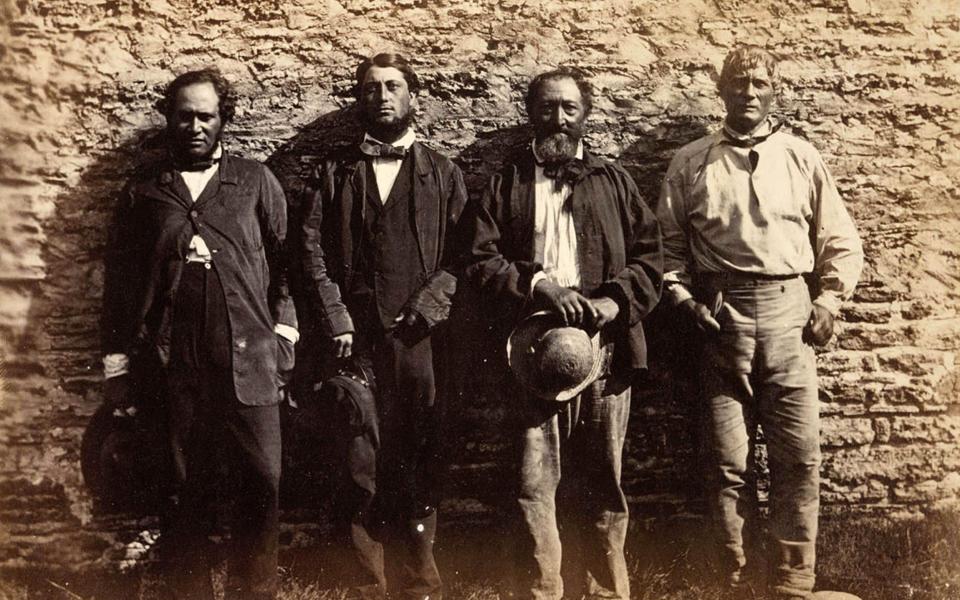

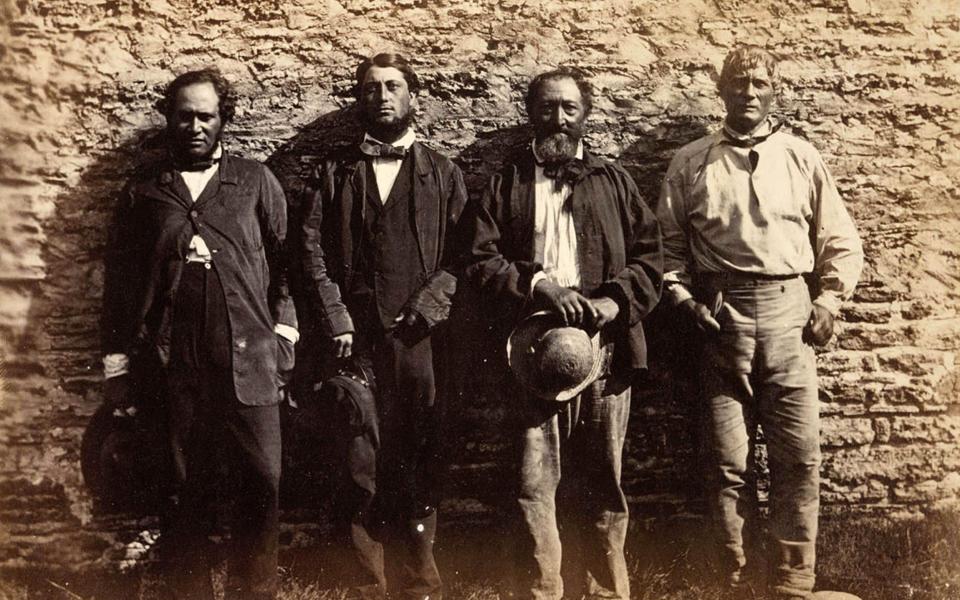

While Polynesians lived on the islands for hundreds of years until the 16th century, Pitcairn was uninhabited in 1790 when it received the arrivals that shaped the island’s modern history. Nine of the mutineers on HMS Bounty, led by Fletcher Christian, went ashore on Pitcairn with 17 native Tahitians and sank their ship behind them. You can see why they were drawn to it; Rising steeply from the sea, Pitcairn resembles both a fortress and a refuge. The mutineers lived from farming and fishing and successfully hid from expeditions that brought them to justice for almost twenty years. The dramatizations of the story, in which Christian is portrayed as a hero and played by Errol Flynn, Clark Gable, Marlon Brando and Mel Gibson, have done little to show the grim reality of the Mutiny or the years that followed, during which the Pitcairners died quickly to disease, murder and alcoholism.

Their presence was not documented until 1808. By this time only one of the original mutineers, John Adams, was still alive with nine wives and nineteen children. When Pitcairn became a regular stop for whaling ships and was incorporated into the British Empire, the population grew, peaking at 233 in 1937. Much of the population is still descended from the original mutineers.

Yet Pitcairn has long been haunted by stories of pedophilia and incest. Three cases of sex with minors were reported in the 1950s. In the late 1990s, a Kent police officer discovered more allegations of abuse. The annus horribilis came in 2004 when seven men, a third of the island’s male population, faced 55 charges of child sexual abuse. All but one were found guilty and imprisoned, including then-Mayor Steve Christian, a Fletcher descendant. Above all, a prison had to be built. The impression, supported by other reports, was of an island with its own moral code and customs – nominally related to its Polynesian heritage – where it was accepted that women over the age of twelve were fair game for sex.

Young says the island has moved on, even if the press hasn’t.

“Twenty years ago it was a different story, it was very divisive, which you would absolutely expect,” he says. “But we have changed the legislation, we have an external police officer, we have had special training. It took a long time to get through it, but we have become stronger. It has been dealt with and is now considered historic. We learned from it, we didn’t sweep it under the rug, we moved on.”

The abuse cases were not the end of Pitcairn’s problems. The country became an unlikely victim of Brexit, which dried up EU infrastructure funding. The pandemic stopped the occasional visit from cruise ships. Almost everything has to be imported, meaning it will never become economically self-sufficient, relying on handouts from the British government: £5 million a year, at last count, or about £125,000 per person.

“The bottom line is that unless we are Guyana and find oil off the coast, we will never be self-sufficient,” says Young. “It looks awful when you look at the population size, but there is no other option than having to cater to the needs of a British Overseas Territory.” He says two-thirds of the money will go to the Silver Supporter, Pitcairn’s special supply ship, which carries people and supplies from the French Polynesian island of Mangareva. Pitcairn remains shockingly remote. The sea journey from Mangareva, 480 kilometers west northwest of Pitcairn, takes 32 hours. Mangareva is a four-hour flight from Tahiti, which is a five-hour flight from Auckland, which isn’t exactly close to London itself.

Young hopes this remote location, modified by a few modern conveniences, will draw newcomers to Pitcairn as it once did him. He grew up in Pickering, North Yorkshire. After ten years in the Air Force he went on a journey and visited Pitcairn in 1992, fascinated, like many visitors, by the history of the Bounty. He found something more enticing: a place where humpback whales blow as they swim by, birds sing in the pine trees and a small, strange community makes it through difficult conditions, riding ATVs along the dusty paths and helping each other. Young moved permanently with his American wife Shirley in 1999, and they became the first people without a Pitcairn connection to be naturalized. It was “not difficult at all” to convince her to come as she is a “natural traveler”.

“What attracted me was the historical interest and the fact that it was so isolated,” Young says. “There was a small community that just survived and clung to the rock. It conjures up these romantic images.

“Picking is just as beautiful, and the people in both are flexible and resilient. I miss the beauty of the seasons that we take for granted in Britain. Ice under your feet, falling autumn leaves, spring. I also miss the British sense of humor, and my mother.” Even his sister never visited him here.

Still, he says he wouldn’t change it for the world: “What I like about Pitcairn is the lifestyle. You have to accept that it’s extremely isolated: there are restrictions if there’s a serious medical emergency and things like that.

“But it has a lot of qualities that may have been lost in the outside world, where you come together for each other when you need to,” he adds. In a world of eight billion people, he hopes that there are a handful of people for whom this life sounds attractive.

Because satellite internet or not, Pitcairn is unlikely to resemble the rest of the world anytime soon. That’s just how the people there like it. The first thing Young looked at after the Starlink was set up? Escape to the countryNaturally.